Please note these are lecture notes designed for an illustrated lecture. Not all the images used in the lecture are included in the notes and therefore the prose may appear a bit clunky at times. The notes are probably more useful for delivery of the lecture than a straightforward read!

In the early months of the first world war, by December of 1914 Germany had captured thousands upon thousands of allied soldiers, French, Russian and British. Amongst those captured from the British were over 2500 Irishmen from exclusively Irish Regiments, the Munster’s, The Leinsters, the Irish Guards, The Royal Dublin Fusiliers, The Connaught Rangers, the Royal Irish Rifles and the South Irish Horse. Regiments predominately raised in the south of Ireland and whose soldiers were overwhelmingly of the Catholic faith.

They were held as prisoners of war in over a hundred different prison camps across the length and breadth of Germany.

For Sir Roger Casement the Imperial German government had moved almost every Irish Catholic prisoner they had, to one single prison of war camp. Limburg, just south-east of Cologne, and it was there that Sir Roger, facilitated by the German Government, went to persuade them to take an oath and betray their loyalty to the British army

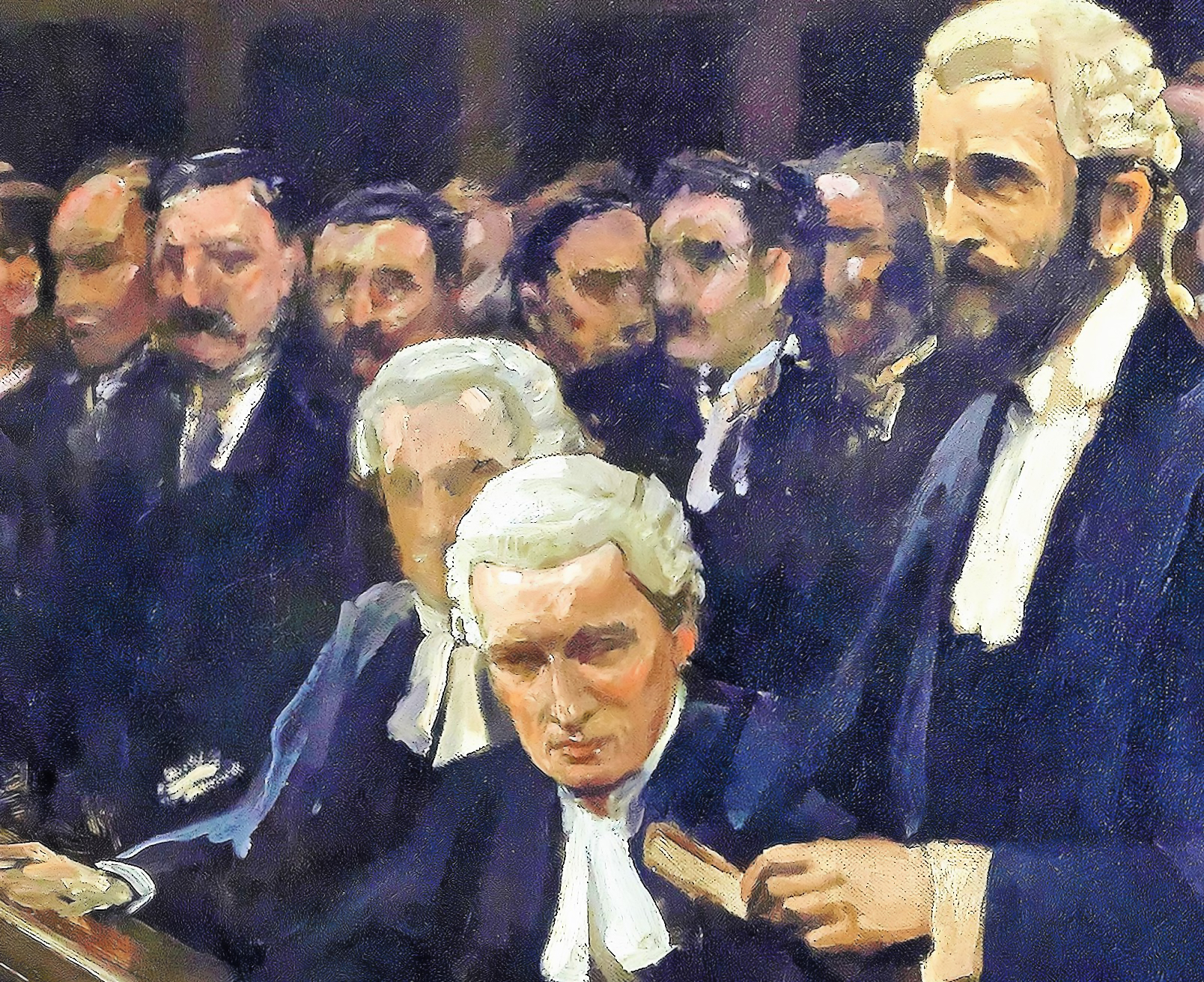

This is a sketch taken from the Illustrated London News. It shows Sir Roger Casement in the very act of attempting to persuade the captured Irish soldiers to desert their British army regiments and join him in what he called an Irish Brigade, formed to fight for Irish Freedom. Those who joined became guests of the German Imperial Government and left the prisoner of war camps to become Irish freedom fighters, allies of the Germans and committed to fighting alongside German troops in an anticipated German invasion of Ireland that was to be timed to synchronize with an Irish Rising.

For the British public, this sketch shows a portrait of an honored and decorated knight of the realm in the very act of committing treason. It is for this he will hang.

From 2500 captured Irish Casement managed to persuade only 56 men to join the Irish Brigade. They were a motley lot and without any officers there are reports of indiscipline, heavy drinking, and fighting, including a football match against their German comrades which ended in a brawl that had to be broken up by the firing of shots. It was really no more than you might expect of any infantry unit, except perhaps for the shots, and there is little doubt they were prepared to fight and if they had ever landed in Ireland they would have given a good account of themselves.

This picture shows the Brigade’s NCO’s in their new green uniforms with, in the middle, one of their German army training officers.

On the eve of the Easter Rising Casement left Germany for Ireland with only one man who had been so recruited. Three men would land on the Kerry coast, at Banna Strand, from the German submarine, U boat19, in which they traveled. There was Casement, of course, accompanied by Robert Montieth who was never a prisoner of the Germans, he was an experienced and trusted member of the Irish Volunteers, and been sent to command the Irish Brigade, and Private Bailey, a soldier from the Royal Irish Regiment who had been captured on the battlefield and was the only volunteer recruited from the prisoners of war who landed in Ireland. There is a famous photograph showing Montieth with an un-bearded Casement beside him and a be-hatted Private Bailey, with members of the U boat crew, on the conning tower of the U-boat from which they landed in Kerry:

Casement was arrested within hours of landing on the Irish shore, his feet and clothing still wet from the sea. Montieth got away. Bailey was captured by the RIC later the same day. Within three months Bailey had turned Kings Evidence and told British intelligence everything he knew about the activities of Casement in Germany and the names and numbers of the recruited soldiers of the Brigade. Within the same three months, he had re-joined the British Army and returned to the War. Only Casement would face the consequences; only he would be convicted of High Treason; only he would stand trial. Only he would hang.

He could have been shot as were the other leaders of the Rising, but instead, he was put on trial for High Treason, in the Royal Courts of Justice. It would be the most important state trial of the 20th Century and we are fortunate indeed to have the great painting of the scene in court, painted by Sir John Lavery, and showing the very court where Casement was tried and convicted for High Treason and where he was sentenced to death.

It is, of course, a painting of the appeal hearing and not the trial itself. But the appeal was heard in the same court as the trial and therefore the only difference between this view and what we would have seen at the trial proper, is that here there are five scarlet-robed judges whereas at the trial there were only three. There would, of course, also have been a jury but on this occasion, for the appeal hearing, the jury box is occupied by the artist John Lavery

The world of legal paintings, of those that adorn the walls and rooms of judges and lawyers, in their offices and Inns, are often, a little like the lawyers and judges themselves, rather dull and rather worthy. They are more frequently noted for their formality rather than as works of art.

Paintings of lawyers and judges actually at their work, inside the courtroom, are rare indeed. And there is simply none of the quality of Lavery’s work.

Of course, one reason why such canvases are rare is that it is illegal to make images inside a courtroom, either by photographic recording or by sketch or painting.

In that respect at least, Casement is quite unique for, in addition to the Lavery painting of him sitting in the Court of Criminal Appeal, there is that famous photograph of him sitting in the dock in Bow St. Magistrates Court, an image which was without any doubt, taken illegally and which is undoubtedly, and probably still is, in contempt of court. We may be committing an offence by merely looking at it.

But it is the Lavery painting that I wish to focus upon. And it is quite wonderful. There is not another legal painting in the entire common law world as fine as this massive, 10 foot by seven-foot canvas.

It is a lawyers painting. It knows of wigs and books, of procedure and of precedent. It captures the life of the law and is as close as we can possibly get to the great historical scene it depicts.

In both England and in Ireland it is in fact not just a painting. It is a rare archival document of immense historical, political social and judicial importance. We should remember it is a real history painting captured by the artist as he sits in the jury box, paints beside him, sketching, drawing, measuring the scene and listening intently to this dramatic moment in the long conflict between England’s laws and Ireland’s destiny.

Most eyes in the Court are drawn towards Judge Darling, the presiding judge. Stern, straight-backed, he commands his courtroom. The painting flatters him. It catches him in a handsome and noble profile.

And so it should. For it was he who commissioned the artist, Sir John Lavery, to paint the scene and it was he who gave him the run of the jury box, throughout the three days of the Appeal, to prepare his sketches and drawings.

They were old friends, Darling and Lavery. A few years earlier, in 1907, Lavery had completed a formal portrait of Darling showing him in full judicial robes and wearing the black cap pronouncing a sentence of death. Again, Lavery produced a work of art outside the usual run of formal legal portraits, but it was a portrait considered by many in the world of the law to be in extremely poor taste, it attracted a great deal of criticism and somewhat confirmed Darling’s reputation for vanity, a reputation well fuelled by another painting he commissioned on the occasion that he was appointed to the Bench. This is not by Lavery but it is rather spectacular.

There is little doubt, in my mind at least, that Darling’s subsequent decision to commission Lavery to capture the Casement appeal hearing, was in part influenced by his vanity. This was Judge Darling’s great bid for legal immortality. A great moment in the law and in history. A famous knight of the realm in the dock. A great state trial. A great artist, and a great judge.

Perhaps he thought he needed such immortality for his appointment to the bench had not been greeted with universal celebration, The London Times had commented that Darling had, thus far, shown no legal eminence at the bar. Many thought his was a political appointment; in a culture, unlike ours in Ireland, which did not and does not promote political appointments. Before his appointment to the bench, he had also been, in addition to a practicing barrister, a conservative Member of Parliament for Deptford in south London.

Despite the criticism, he enjoyed a successful career on the bench. He became known for his judicial wit and was fond of mixing with poets and artists. He even wrote a rather good book of verse. He was at one stage, in 1922, considered as a replacement for the post of Lord Chief Justice of England. He was at the time 73 years of age, but he was passed over for the appointment in favour of A.T. Lawrence, who was aged 78. Darling used to say he was rejected for the post because he was too young.

Lawrence sat with him at this appeal hearing as one of his appeal judges and is seated immediately on Darlings left.

As a conservative MP Darling had consistently voted with the unionists against Home Rule. He was a close friend of Edward Carson and it was he who had invited Carson to join his barrister’s chambers when Carson transferred from the Irish to the English Bar. Carson was a member of his chambers when he acted for the Marquis of Queensbury against Oscar Wilde. Darling considered Carson, unlike most other Irishmen that he knew in that he was an Irishman completely incapable of speaking balderdash. What that says for the rest of you might indicate a degree of judicial bias. However, it cannot be said that his unionist sympathies influenced his decision on the legal arguments advanced on behalf of Casement. The law was too heavily against them.

If the presiding judge at the appeal was a unionist sympathiser then the same is true, with spades, of the leading counsel for the prosecution. F.E. Smith, the Attorney General, shown here having his attention drawn to a law report.

Smith had signed the Ulster covenant in the City Hall at Belfast. His entire political history made him a deeply orange unionist. He owed his parliamentary seat to an Orange area of Liverpool, Birkenhead. He was known as Carson’s galloper, effectively Carson’s second in command. Here he is shown with Carson reviewing the Ulster volunteers with the guns they had run into the North and had landed at Larne.

At least one, if not more of his speeches for the Ulster volunteers, had been described, by Winston Churchill, as promoting naked revolution against parliamentary rule. Even his birthday was on the anniversary of the Battle of the Boyne!

In Casement’s final speech from the dock,* he made a direct attack upon Smith, saying that he, Casement, had chosen the path that he knew would lead to the dock whilst the unionist champions had chosen the path that would lead to the woolsack.

And he was right. F.E. Smith did reach the woolsack. Becoming 1919, Lord Chancellor of England, taking his title from his orange constituency in Liverpool and becoming the Earl of Birkenhead.

It has always been questionable whether F.E. Smith, given his political background, should have prosecuted in this case. He, of course, had no doubts about it at all. He was Attorney General, and not to have prosecuted would have been to acknowledge, perhaps, his own role in the arming and support of the Ulster volunteers as being some kind of equivalence to the Treason of Casement.

I should like to refer briefly to two judges who do not appear in this painting but who presided over the trial proper, in this same Courtroom, about three weeks earlier.

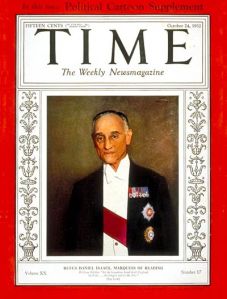

The first was no less than the Lord Chief Justice of England, Lord Reading, also known as Rufus Isaacs, He was Jewish and no Jew had ever before, risen so high as he did in the English Judiciary. He had been a Liberal member of parliament, but he was also known as a friend of Carson.

He had, by the time of this trial, already been to America to negotiate a huge war loan for the British Government, to be used to buy arms from American factories, for the war in Flanders. Which perhaps partly explains why the Americans thought enough of him to put him on the front cover of Time magazine. Later he became the British Ambassador to the United States of America whilst still Lord Chief Justice, and subsequently, he was appointed as Viceroy of India where he is remembered for amongst many other things, for the imprisonment of Mahatma Gandhi.

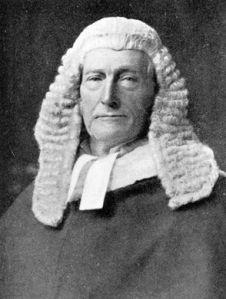

Lord reading was assisted in the trial by Mr. Justice Avory and Mr. Justice Horridge.

Avory is of particular interest to us. As a practicing barrister, he had been one of the most noted criminal lawyers of his time. As a judge he had a reputation as a dreaded “hanging judge” He was described as “thin-lipped, cold, utterly unemotional. And I think his photographic portrait somewhat captures those qualities.

But his great interest to us is that he had previously, in about 1902, acted in the defence of another Irishman accused of High Treason.

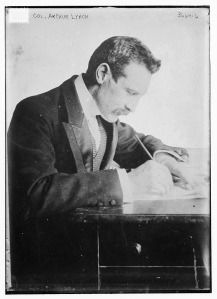

That man was the Australian born Irishman, Colonel Arthur Alfred Lynch, who had commanded an Irish Brigade against the British during the Boer War.

After the Boer War, Lynch, without ever setting foot in Ireland, he was living in France, was elected the Member of Parliament for Galway. When he traveled from Paris to London to take up his parliamentary seat he was arrested as he stepped off the boat at Dover, and charged with High Treason for his adventures in South Africa.

He was prosecuted by Carson who was then Solicitor General and defended by Avory K.C. Avory advanced the ingenious defence that the 1351 Statute of Treasons, under which Lynch was charged, disclosed no offence because it only applied to acts committed within the realm, and as Colonel Lynch’s treachery had occurred without the realm, in South Africa, then the statute did not apply.

It was of course exactly the same defence as would be advanced by Casement. It would be rejected in Lynch’s case, as it would be in Casements. Lynch was found guilty of High Treason and sentenced to death, but unlike Casement, his sentence was commuted to life imprisonment and eventually he was released on license, whereupon he was elected MP for Clare West and was commissioned into the military in order to conduct a recruiting campaign for the British Army in Ireland.

Now, at Casement’s trial, Avory would listen to Casement’s counsel arguing exactly the same point as he had himself argued and lost in the Lynch case. When it is said of the Casement defence that the law was against them then we can be sure no one else involved in the trial would know that better than would Avory.

It is my belief that Casement’s defence team were hoping for a similar result, that is, they knew from the start that the hope of a finding of not guilty was fairly hopeless, but that they could present Casement in such a light that appeals for clemency might prevail. That he might escape the gallows and might yet play a role in the destiny of Ireland.

But back to the appeal for there are a wealth of interesting characters here, and little time to describe them all. I want to point out Bodkin, Junior Counsel to F.E. Smith; he is drawing F.E.’s attention to some legal point in one of the books of law, perhaps to Lynch’s case.

Bodkin was subsequently appointed Director of Public Prosecutions and is noted for his role in the banning of James Joyce’s Ulysses, being convinced that the soliloquy of Molly was sufficient to deem it obscene. The ban in English law was not lifted until 1938.

I should mention too Judge Aikin, for he is so famous a judge that there is not a student of law or a practicing barrister, solicitor or judge anywhere in the common law world who has not at some time in their legal careers quoted this judge who made one of the most important speeches ever in the law of negligence when he acted as an appellate judge in the case of Donohue v Stephenson. For those of you who are not lawyers, it concerned the rather mundane case of a snail having been found in a bottle of ginger beer. Dull enough stuff, I know, but Akin is to the law as Arthur is to Guinness. He sits at the very end of the judges’ bench and It is a great pity that the painting does not capture his features better than it does. He sits on the very end of the line of the five appeal judges.

We should never, of course, forget that this trial was conducted in the middle of the most gruesome war. Many from the English Bar, and indeed from the Irish Bar, had abandoned the law for the Trenches and quite a few would not return. And almost no one in England was left untouched by the causality lists published each day in the London Times and other newspapers, Scrutton, the first judge on the bench, or the one nearest to us, was both a judge and a Professor of Constitutional Law and Legal History. He had already lost his younger son to the trenches and one can well imagine his mixed feelings towards Casement who had been seeking to suborn soldiers from their allegiance to their regiments and to the crown, in whose service his son had so recently fallen.

Turning to the Irish we must of first of all pay tribute to Gertrude Bannister, cousin of Casement, to whom fell all the initial work of organising for him a solicitor and legal team. She had been a primary teacher at a school but lost her post, after 13 uninterrupted years of service, because of her involvement with the traitor casement. But she never missed a day of the trial or the appeal, never missed the opportunity of a visit to Casement in his various prison cells and never ebbed in her unequivocal support for him. She is glancing up at Casement in the dock – and I think he is glancing down at her. They were devoted to one another and I suspect the artist, who knew of her devotion to Casement, has tried to capture it in the glance they exchange. She was his most trusted friend in court.

The other women are Alice Stopford Green and the wife of the solicitor Gavan Duffy. Alice had been involved in the Howth gun-running, as indeed had Casement. They were close friends. She was a passionate nationalist historian, and it was she that Gertrude Bannister first approached for help on learning of her Roger’s capture and imprisonment in the Tower of London. And it was she who introduced Gertrude to the solicitor Gavan Duffy.

Gavan Duffy, Casement’s solicitor, came from the most admirable nationalist stock. His father was a prolific Irish historian and nationalist, a founder member and editor of the Nation newspaper and a leader of the Tenant League;, he had stood trial with Daniel O’Connell, had participated in the 1848 Ballingarry rising. He was a dynamic promoter of Irish constitutional nationalism.

He subsequently left Ireland for Australia where became Governor General of Victoria and was knighted as Sir Charles Gavan Duffy. He introduced a land Act in Australia, carved from his experiences of the Irish Land Law, and known in Australia as the Gavan Duffy Land Acts. The family of Ned Kelly, were, at the time of Ned’s adventures with the Australian Police, being considered for a grant of Land under the Gavan Duffy Land Acts.

His son, George Gavan Duffy, now Casement’s solicitor, was English educated, at the Stonybridge Catholic public school, and had a cut glass English public school accent. At the time of Casement’s arrest, when he was approached by Gertrude Bannister and Alice Stopford Green, he was enjoying a prosperous career as a partner in a London firm of solicitors. The other partners could not stomach his involvement with the traitor Casement and gave him the choice of staying with the firm or resigning from the partnership to defend Casement. To his eternal glory, as a both an Irishman and a lawyer, he chose his client. He is one of my legal heroes; indeed I named one of my sons after him.

The trial completely changed his direction in life. From a prosperous English solicitor’s practice, he turned to revolutionary nationalism. He was sent by de Valera along with Collins, Griffith, Barton, and Duggan to conduct the treaty negotiations. There he would have met again, F.E. Smith now negotiating on the British government team.

In the new Irish Government of the Free State, Duffy was appointed as Minister of Foreign Affairs. He resigned his seat over the refusal of the Free State to treat captured anti-treaty Republicans as prisoners of war. He then returned to the Law, transferred to the bar and rose to become President of the High Court of Ireland. His other brother, living with his father in Australia rose to become Chief Justice of the High Court of Australia. The portrait of Gavan Duffy is also by Lavery.

Gavan Duffy had an incident-packed glittering career and there is a great biography waiting to be written on him. It will have to include, unfortunately, a judgment he made in 1944 and known as the Schegal case in which he found that it was reasonable and lawful for a Christian landlord to discriminate against a Jewish tenant. I did not know that when I named my son. I may have named him after an anti-Semite,!

While we cannot ignore the Schelgal judgment, he remains, I think, one of the legal heroes of the Casement story.

Gavan Duffy wanted, as we all know, a senior English Kings Counsel to conduct the defence. One of the more disturbing professional elements of the trial is the story that he was unable to find a Kings Counsel of the English bar willing to take the case on.

It was a time of war, and there is little doubt that there would be some element of distaste in defending a traitor in the middle of a war, but that is no excuse and the story runs against the traditions of the bar, in both England or in Ireland, where it would, in either jurisdiction, be abhorrent to refuse a case on such grounds. The story is not in fact supported by any substantial documentation. It was hinted at in a Dublin lecture Gavan Duffy gave in April 1950 to the London-Irish Gaels, but there are not, at least to my limited knowledge, any letters or documents corroborating the story. In fact, there is more evidence to put the story into serious question than there is to support it. For example, Gavan Duffy had no difficulty in finding Junior Counsel from the English Bar. Indeed he had two Junior Counsel. Jones and Morgan. Neither suffered for their role in representing a traitor. Morgan was at the time a commissioned officer in the British Army, a Brigadier no less, and found no inhibition in representing a man tried for treason. In the second world war, he became an adviser on constitutional law to Winston Churchill Jones was, in 1930 himself appointed to the bench. And he was knighted in 1931

Thomas Artemous Jones first appeared for Casement at the Bow-street magistrates Court. e also appeared here in this court at the trial proper and he is here again, in the appeal, sitting beside his leader, the bearded Sullivan.

Jones is remembered in the law more for a case in which he was a litigant than in any in which he appeared as counsel. The case remains a leading authority in the law of libel and is often quoted in today’s courts both in England and in Ireland. A newspaper reporter had filed a story about Englishmen holidaying in France. He described what he thought was a fictional character called Artemous Jones, drinking a glass of wine with a woman who, he reported, was not his wife. The reporter, rather naturally believed that no one on earth could possibly be called Artemous Jones, but of course, he was wrong.

Unable to secure the services of a Senior member of the English Bar, Gavan Duffy turned to the Irish Bar and appointed the Irish barrister Alexander Sullivan, who was also his brother in law. (There is a somewhat ancient tradition at the Irish Bar which keeps valuable work in the family) Sergeant Sullivan was a Kings Counsel of the Irish Bar, but at the English Bar, he was merely a Junior Counsel of sixteen years standing. He was therefore not allowed to occupy the front bench for barristers, that being reserved for Senior Counsel, as it still is today. So we see him addressing the court from the second-row bench, alongside his juniors.It would be unfair not to mention that F.E. Smith did try to have Sullivan appointed as an English Silk in order that there would be no disparity of appearance in the fighting of the trial, but the request was denied by the Lord Chancellor – they had adopted a policy of not appointing any more silks for the duration of the war.

The office of sergeant meant that Sullivan was a member of a superior order of barristers from whose ranks were chosen the common law judges. Had Ireland not become independent he was undoubtedly destined for the Irish Bench.

Their only distinguishing mark of a sergeant at law was a small patch of black silk set into the top of the wig. They were crown law officers and could not in the normal course of events take a brief against the Crown. But Sullivan was encouraged by Chief Baron Palles to accept the brief. He did so but without any great enthusiasm. He wrote to Gavan Duffy saying he would take on the trial providing he was well paid. In the event, he was paid £630 for the trial, which lasted five days, and a further fee for the three days of the appeal. The money was raised through private donations from amongst others, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, the Quaker William Cadbury, George Bernard Shaw and with a large sum raised in America by the legendary revolutionary John Devoy of Clan Na Gael. The American money was brought over to England by the U. S. lawyer Francis Doyle, who somewhat unusually was granted permission to assist the defence team. He sits beside Gavan Duffy on the solicitor’s bench. Montgomery Hyde, in his important book of this trial, records that the German Secret Service subsequently reimbursed this American money to Clan na Geal..

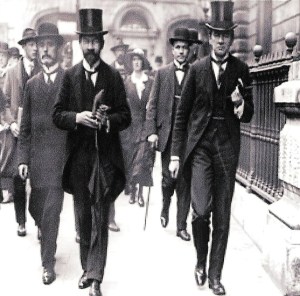

I find it difficult to exclude this wonderful photograph of Gavan Duffy, Casement’s solicitor, and Artemous Jones, his junior counsel, arriving at the Royal Courts of Justice for the trial. I do so only to note how far the sartorial standards at the bar have deteriorated over the years.

At the actual trial, here in the same courtroom, Sullivan had delivered a surprisingly eloquent summing up to the jury; he would have been facing us, as he delivered it. We are the jury. He sought to argue that nationalist Ireland had been engaged in arming itself solely to defend against and defeat the threats to home Rule emanating from the already heavily armed Unionist Ulster volunteers.

It was a stirring speech and is my view much underrated. It would have caused some particular discomfort to F.E. Smith.

The speech made much of the limited material available to him from the evidence that had been offered.

In fact a bit too much.

He was interrupted by the Chief Justice, Lord Reading, and by F.E. who both protested he was introducing arguments to the jury that were not supported by any evidence offered by the many witnesses that had been called. He made a rather poor attempt to say the evidence had been given, by the RIC officers. But the Chief Justice made a distinction in that the gun-running that occurred in Ireland prior to the declaration of war with Germany was not the same as gun-running during a time of war with Germany when Germany had paid for the arms and organised their delivery.

Perhaps he was over deferential but the interruption affected him greatly. He acknowledged he was wrong and was obliged to apologise to the Lord Chief Justice. He lost the thread of his argument and in attempting to resume, he lost it altogether, He swayed unsteadily on his feet, and collapsed into his seat saying “ My Lords I cannot go on.”

The trial was immediately adjourned and when it continued next day Sullivan was still unwell and absent from the court. The rest of his closing speech was completed by his junior Artemous Jones.

The prisoner was not impressed!

Why did he falter?.

The general position of most who have examined this trial is that he was exhausted and genuinely unwell. But it has to be observed that it seems an extraordinary omission for the Defence not to have seen the distinction between gun-running in time of peace and gun-running in time of war. An English jury might possibly understand the desire of the Irish to arm themselves to protect against the wish of the Ulster volunteers to try to destroy the democratic wish of parliament for Home Rule. But gun-running, from the enemy, in time of war was difficult to explain. I rather suspect that Sullivan realised this and that his collapse is one of those moments in the Irish story where constitutional nationalists began to understand that for them, the game was over and that history and the guns had passed to men with different and revolutionary aims. Perhaps he stumbled over Irish History.

But as we can see, nineteen days later Sullivan was fully recovered and we see him on his feet, addressing the appeal court.

The defence argument advanced by Casement’s team was the same as that advanced by Avory in the trial of Colonel Lynch. Exactly the same. It failed for Lynch and it failed for Casement.

Briefly, it centered upon an interpretation of the 1351 Treason Act under which Casement was charged. The Act envisaged that treason should occur “within the realme” The statute was written in Norman French, without any punctuation. Judge Darling and Judge Aitkin had examined the original document at the Public Records office, which at the time was just next door to the Royal Courts. They dismissed any submission that suggested it should be interpreted with commas that restricted treason to Acts within the Kings Realm. Casement wrote to a friend saying that it was if it was to hang a man’s life upon a comma and throttle him with a semi-colon.

It is difficult to believe that anyone on the Casement defence really believed that such an argument would prove successful. It is true that Brigadier Morgan, part of the defence team and an English barrister unafraid to defend a man charged with treason even though he held a commission in the Kings Army, had conducted deep research on the ancient statute had told Sullivan he had effectively dismissed all the existing authorities, but he was of course wrong. The authorities were nearly all against them and were of such quality, Coke, Hail, Fitzherberet, writers and judicial commentators acknowledged as the most eminent ever known to English Law.

Alice Stopford Green was the most consistently realistic of those who helped in the trial. She always saw it not as a trial from which Casement could escape, but as a process which might lead to a reprieve. If it was handled well, Casement might escape the rope, as had Lynch; he might yet be saved.

George Bernard Shaw had urged Casement to dispense with his lawyers and use the trial to make great speeches about Ireland; to refuse to recognise the court and demand a trial before Irishmen in Ireland. He was to tell the court he was an Irishman captured in a fair attempt to free his country.

Shaw was writing for the theatre, perhaps for history, but the legal team was fighting for a life and in reality, if they were to stand any chance of a reprieve from the death sentence then an argument on the technicalities of the law was all that was open to them. The hard evidence was overwhelming and the Court would have quickly brought to an end any attempt to use the trial for a political end or to allow the trial to descend into passion.

In truth, the defence could not afford to put Casement up for cross-examination. He was not in the best of health and in any case he had already admitted almost everything in interviews with British intelligence. Any half competent cross-examiner would have exposed him as deeply pro-German, anti-patriotic and anti-British and in the process destroyed any possible hope of reprieve. In fact, it was not a question of putting him up against any old half competent cross-examiner. He would be required to face the finest cross-examiner then practicing in English law. F.E. Smith would most certainly have destroyed him and hastened his journey to the gallows.

So, in due course, without even requiring F.E. Smith to reply to Sullivan’s appeal submissions on behalf of Casement, Darling dismissed the appeal and the court confirmed the sentence of death

There should have been a further appeal, this time to the House of Lords, but such an appeal needed the consent of the Attorney General.

F.E. refused his consent, arguing that between the trial and the appeal, eight of the most senior and eminent judges in England had unanimously rejected the defence argument, and that was enough.

The defence team was devastated. More so than Casement himself, who was by now reconciled to his fate. Their constitutional law expert, Professor Morgan, (the Brigadier was also a professor) wrote to F.E. that he had consulted Sir William Houldsworth, then the greatest legal scholar known to the law, and that Houldsworth was in agreement that an important point of law existed that merited a hearing before the House of Lords. It is said that upon hearing the great scholar’s opinion, F.E. Smith remarked “ I am well acquainted with the legal attainments of Sir William Houldsworth. He was, after all, runner-up to me in the Vinearian prize for law students when we were at Oxford.”

There was another point of appeal filed by the Defence team for argument before this Court but not pursued. It accounts in part, I suggest, as to why the courtroom is so crowded with lawyers. At the trial, in his summing up to the Jury, the Lord Chief Justice had directed that”..as a matter of law, that if a man, a British subject, does an act which strengthens, or tends to strengthen the enemies of the king in the conduct of the war… …then that is in law the giving of aid and comfort to the Kings enemies”

It was an extraordinarily wide and sweeping interpretation of treason, and meant, as Casement wrote in a note to his counsel, that it would leave no loophole of escape from the charge of High Treason to any conscientious objector, or liberal writer, or Christian clergyman within the realm.

So a further point of appeal prepared for Casement was to challenge the Judge’s charge to the jury.

It must have spread like wildfire through the Royal Courts of Justice, that this unknown, Irish Barrister was about to challenge the charge to the jury made by the very Lord Chief Justice of England. No wonder the lawyers crowded in.

In the event, Sullivan did not pursue the point of appeal. He made that decision upon his own and without instructions from his client or his solicitor. Casement was very angry about it, so too was Gavan Duffy and he, rather imprudently, made his unhappiness known, albeit informally, to other members of the English Bar. Casement thought Sullivan had played him a sad trick and that he would have been better off making do with the two Welshmen, Artemous Jones, and Professor Morgan.

In any event, Darling, hearing about the disquiet, reconvened the Court of Appeal to hear any further points of appeal that might be made. The prosecution team appeared but the defence did not. Nothing else was heard of the matter.

All that was now left were appeals for clemency. It was not the conduct of the trial that defeated such claims. It was the diaries.

The diaries contained explicit descriptions of Casement’s life as a homosexual and they were widely circulated to destroy his reputation and reduce the number of petitioners for clemency.

If you were to compare Casement’s grounds for clemency against those of Colonel Lynch, then hopes must have been high. Lynch had led armed men against the British in the field. He had killed soldiers of the crown. Casement had not. Casement had an international reputation as a humanitarian. Lynch enjoyed no such reputation. Casement had been knighted for his humanitarian work; his network of friends arising from his work in the Congo and in Putumayo was vast and international. The calls for clemency should have been equally vast and equally international. But it was the diaries that destroyed the attempts to engage the vast network of support.

Those involved in the trial had little to do with the circulation of the diaries. Some doubt may still stick to F.E., but generally, all who were involved with the trial and the appeal, and who subsequently wrote about it say it was a remarkably fair trial. It was certainly no kangaroo court. Every fact relied upon for conviction was proved by witnesses brought over from Ireland and the trial was conducted as fairly as any criminal trial before the English Courts. They even had repatriated prisoners of war who testified to their personal knowledge of Casement at work in the prisoner of war camps.

The diaries were deployed by the state authorities, not by the law. By the secret service, the politicians, the cabinet. They were designed to undermine Casement’s integrity and destroy his reputation and his hope of escaping the rope. They were spectacularly successful and prevented many supporters, including the American government from weighing in on behalf of Casement. They succeeded in adding the fatal weight to the hangman’s rope. But they also succeeded in undermining the integrity of this trial and the integrity of English justice. They made this painting an unacceptable celebration of the law. It became a troublesome portrait, which in the end, I think, the British were glad to see the back of.

Lavery, as we can see has placed Casement at the very centre of the canvas. He is the primary point of focus. Lavery was an Irishman himself, born in Belfast and brought up, partly in Antrim but mostly in Scotland. He studied Art, part-time, in Glasgow using his income as a photographer’s assistant to pay for the lessons. Although he became the most famous portrait painter of his time and a leading member of the “Glasgow Boys” school of Art, he was always conscious of his Irish origins. In later life, after he married Lady Lavery, he painted a wide range of Irish portraits. Collins, De Valera, Cardinal Louge, Grittiths Duggen. He painted all the participants, from both sides, who took part in the treaty negotiations. His wife Lady Lavery is claimed to have played a pivotal role in persuading Collins to sign the treaty, she was most certainly in love with Collins, In his biography, Lavery claims that his wife was to join him when he was to be appointed as viceroy of the new Ireland following the enactment of the treaty. It seems a serious claim. Winston Churchill, who she taught painting techniques, was certain it would happen. The nomination was to be made by O’Higgins, and the nomination died with his assassination during the civil war.

Although the painting was commissioned by Lord Darling, it was left on Lavery’s hands. At his death, he willed the painting to the Royal Courts of Justice. Actually, he left it first to the National Gallery, if they refused it then to the Royal Courts and if they refused it then to the National Gallery of Ireland. The Royal courts accepted it, but without, I think realising it was so large. In addition, as a result of the controversies over the diaries the value of the painting, as a record of a great English legal moment, had become somewhat tainted. That is probably the reason why it had been left on Lavery’s hands in the first place.

The English refused to hang it in a public place in the Royal Courts, perhaps instinctively recognising that it celebrated Casement more than it celebrated the English Law. It was hung in a basement office. No one visited that office and no one saw the painting and over time, its subject and importance were quickly forgotten.

In the 1950’s Sgt Sullivan retired from the English Bar and came home to live in Dublin, where he was made an honorary bencher of the Kings Inns. He wrote to the English on behalf of the Kings seeking to buy the painting. His letter provoked an interesting exchange of correspondence between the English Lord Chancellor and the English Lord Chief Justice. The Lord Chancellor wrote, “we can adopt the suggestion of lending it to the Kings Inns on indefinite loan which means we can forget to ask for its return.” He also wrote to Sgt Sullivan saying the loan was repayable on demand but adding, that any such demand is unlikely to be hurried.

So now we have it. Hanging in the Kings Inns, designed in vanity as a tribute to Lord Darling and the English Law but serving instead, as an enduring tribute to an Irish patriot. There are other versions of the painting, but none so grand as this. The municipal gallery in Dublin owns a much smaller copy, prepared as a study for this larger canvas. It used to be on permanent loan to President McAlesse, being one of her favorite paintings. That version shows the artists wife, the beautiful Lady Lavery, seated in the gallery wearing one of trademark large hats. It is the version referred to in Yeats poem, “On a visit to a municipal gallery.” The smaller version allows us, I think, to see how Lavery’s interest and empathy with the Irish issue developed as he worked on the larger canvas. In the smaller, Hugh Lane canvas, we can see the windows of the court but the light from the windows is even and rather flat. In the larger, Kings Inn’s canvas, he has allowed the light to stream down and flood Casement as he sits in the dock, giving him a prominence he simply does not have in the Hugh Lane version

Those of us, barristers of the Irish Bar, who are privileged to be able to view this painting so often, and at such close quarters, owe a great debt to Sgt Sullivan. He may not enjoy a reputation of having handled the trial as well as he should have, but in obtaining for us the painting, and doing so in terms which effectively mean it will stay with us forever, he performed an act of great service to Ireland.

I might before finishing urge you, should you have found this of any interest, to go to the Royal Courts of Justice and visit the courtroom wherein Casement was sentenced to death. It is courtroom 36 in the West Green wing of the Royal Courts of Justice, take with you if you do, a copy of this great painting, and you will observe, with the hairs rising on the back of your neck, how little the courtroom has changed this hundred years or so; you will be aware you are in a place of death, a place of history and perhaps, a place of pilgrimage

The notes herein (but not the images) are copyright of the author John McGuiggan Barrister at Law. ( johnthebarrister@gmail.com )

*Roger Casement’s Speech in Court Following his Conviction as a Traitor

As I wish my words to reach a much wider audience than I see before me here, I intend to read all that I propose to say.

What I shall read now is something I wrote more than twenty days ago. There is an objection possibly not good in law but surely good on moral grounds against the application to me here of this English statute, 565 years old, that seeks to deprive an Irishman to-day of life and honour, not for “adhering to the King’s enemies” but for adhering to his own people.

When this statute was passed, in 1351, what was the state of men’s minds on the question of a far higher allegiance – that of man to God and His Kingdom?

The law of that day did not permit a man to forsake his Church or deny his God save with his life. The heretic then had the same doom as the traitor. Today a man may forswear God and His Heavenly Realm without fear or penalty, all earlier statutes having gone the way of Nero’s edicts against the Christians; but that constitutional phantom the King can still dig up from the dungeons and torture chambers of the Dark Ages a law that takes a man’s life and limb for an exercise of conscience.

Loyalty is a sentiment, not a law. It rests on Love, not on restraint. The government of Ireland by England rests on restraint and not on law; and, since it demands no love, it can evoke no loyalty. Judicial assassination today is reserved only for one race of the King’s subjects, for Irishmen; for those who cannot forget their allegiance to the realm of Ireland.

What is the fundamental charter of an Englishman’s liberty? That he shall be tried by his peers. With all respect I assert that this court is to me, an Irishman, a foreign court – this jury is for me, an Irishman, not a jury of my peers.

It is patent to every man of conscience that I have an indefeasible right, if tried at all under this statute of high treason, to be tried in Ireland, before an Irish court, and by an Irish jury.

This court, this jury, the public opinion of this country, England, cannot but be prejudiced in varying degree against me, most of all in time of war. From this court and its jurisdiction I appeal to those I am alleged to have wronged, and to those I am alleged to have injured by my “evil example,” and claim that they alone are competent to decide my guilt or my innocence.

This is so fundamental a right, so natural a right, so obvious a right, that it is clear the Crown were aware of it when they brought me by force and by stealth from Ireland to this country. It was not I who landed in England, but the Crown who dragged me here, away from my own country, to which I had returned with a price upon my head, away from my own countrymen, whose loyalty is not in doubt, and safe from the judgment of my peers, whose judgment I do not shrink from.

I admit no other judgment but theirs. I accept no verdict save at their hands.

I assert from this dock that I am being tried here not because it is just, but because it is unjust. My counsel has referred to the Ulster Volunteer movement, and I will not touch at length upon that ground, save only to say that neither I nor any of the leaders of the Irish Volunteers, who were founded in Dublin in November, 1913, had quarrel with the Ulster Volunteers as such, who were born a year earlier.

Our movement was not directed against them, but against the men who misused and misdirected the courage, the sincerity, and the local patriotism of the men of the North of Ireland. On the contrary, we welcomed the coming of the Ulster Volunteers, even while we deprecated the aims and intentions of those Englishmen who sought to pervert to an English party use – to the mean purposes of their own bid for place and power in England – the armed activities of simple Irishmen.

We aimed at winning the Ulster Volunteers to the cause of a united Ireland – we aimed at uniting all Irishmen in a natural and national bond of cohesion based on mutual self-respect. Our hope was a natural one, and, if left to ourselves, not hard to accomplish.

If external influences of disintegration would but leave us alone, we were sure that nature itself must bring us together. It was not the Irish Volunteers who broke the law, but a British party.

The Government had permitted the Ulster Volunteers to be armed by Englishmen to threaten not merely an English party in its hold on office, but to threaten that party through the lives and blood of Irishmen. Our choice lay between submitting to foreign lawlessness and resisting it, and we did not hesitate. I for one was determined that Ireland was much more to me than empire, and that if charity begins at home so must loyalty.

Since arms were so necessary to make our organization a reality and to give to the minds of Irishmen menaced with the most outrageous threats a sense of security, it was our bounden duty to get arms before all else.

I decided with this end in view to go to America. If, as the right honourable gentleman, the present Attorney General, asserted in a speech at Manchester, Nationalists would neither fight for home rule nor pay for it, it was our duty to show him that we knew how to do both.

Then came the war. As Mr. Birrell said in his evidence recently laid before the Commission of Inquiry into the causes of the late rebellion in Ireland, “The war upset all our calculations.”

It upset mine no less than Mr. Birrell’s, and put an end to my mission of peaceful effort in America. War between Great Britain and Germany meant, as I believed, ruin for all the hopes we had founded on the enrolment of the Irish Volunteers.

I felt over there in America that my first duty was to keep Irishmen at home in the only army that could safeguard our national existence. If small nationalities were to be the pawns in this game of embattled giants, I saw no reason why Ireland should shed her blood in any cause but her own, and if that be treason beyond the seas I am not ashamed to avow it or to answer for it here with my life.

And when we had the doctrine of Unionist loyalty at last, “Mausers and Kaisers and any King you like,” I felt I needed no other warrant than that these words conveyed – to go forth and do likewise. The difference between us was that the Unionist champions chose a path which they felt would lead to the Woolsack, while I went a road that I knew must lead to the dock.

And the event proves that we were both right. But let me say that I am prouder to stand here today in the traitor’s dock to answer this impeachment than to fill the place of my accusers. If there be no right of rebellion against a state of things that no savage tribe would endure without resistance, then am I sure that it is better for men to fight and die without right than to live in such a state of right as this.

Where all your rights become only an accumulated wrong; where men must beg with bated breath for leave to subsist in their own land, to think their own thoughts, to sing their own songs, to garner the fruit of their own labours – and even while they beg to see these things inexorably withdrawn from them – then surely it is a braver, a saner, and a truer thing to be a rebel in act and deed against such circumstances as this than tamely to accept it as the natural lot of men.

My Lord, I have done. Gentlemen of the Jury, I wish to thank you for your verdict. I hope you will not think that I made any imputation upon your truthfulness or your integrity when I said that this was not a trial by my peers.

brilliant, a highly stimulating piece. Packed with very useful information, it has helped me answer many questions i’ve been curious about. I’ve been almost in love with this great work of art, -Lavery’s best i think (and that’s really saying something) – since i first saw it at the Kings Inns a few years back. Then of course it was in the Hugh Lane, near the smaller version there you allude to above. Now of course it is currently in the NGI in the Creating History exhibition, where even among some superb pieces, including works by van Wyck, by Orpen by Keating and indeed among 3-4 other workss by Lavery himself, it is, inevitably, the standout work. Anyway, thank you. Superb stuff. I am indebted to you Mr McGuigan. I shall in time re-blog this piece, if I may?

best wishes – Arran Henderson.

Please do. .

Reblogged this on Arran Q Henderson and commented:

This excellent piece will be of particular interest to anyone who was on my recent private tour of the Creating History tour of the National Gallery (last Thursday 15/12/16) But anyone with an interest in 20thC Irish history will savour this.. Enjoy.

Found your writting about Sir Roger casement fascinating I have been to his grave in Dublin your whole article about the defence and prosecutors has left me with more in site.

Thank you.

Very interesting reading for anyone who loves irish history

Regrettably I missed your lecture in Rome owing to illness. However the “notes” are extremely interesting and I congratulate you. Just a couple of points —

1. So the painting referred to by Yeats in “The Municipal Gallery Revisited” is a copy and not Lavery’s original?

2. I’m not clear as to the relevance of Casement’s “deathbed conversion” , can you elaborate.

Again I really wish i’d made it to the Irish College, I obviously missed a very special evening!

The Municipal Gallery painting is certainly by Lavery and is certainly an “original”. It was completed as a study for the much larger canvas and you can see the striking difference/development that took place as he then worked on the larger canvas, particularly in allowing the light from the windows to fall on Casement and give him a prominence he simply does not have in the study.

As to his deathbed conversion I attach below an extract from the Rome lecture which I hope assists you in in clarifying what is meant.

“He walked to the gallows at Pentonville on the 3rd August 1916. He was on the prison’s death row for only 16 days. He had already asked that he receive instruction to allow him to convert, before his execution, into the Roman Catholic faith.

Permission to allow this rested with the curia of the Diocese of Westminster. They decided, it would have been Archbishop Francis Bourne, I think he became a Cardinal in 1911, they decided that the church would only allow him to receive instruction if he signed a document apologising for any scandal he had caused. Casement was concerned about what was meant by scandal, as were the two prison chaplains through whom the request for conversion, the convert form, had been submitted to the curia.

Initially he signed as requested but then, after a restless night’s sleep he withdrew his consent and tore up the document. I think hardly surprising, he did know what scandal was being referred to and had no knowledge as to how such a document might be used following his execution. He could not leave such a document behind him.

As a result the diocese would not facilitate his instruction or receive him into the faith.

The prison chaplains decided therefore to reconcile him back into the church on the night before his execution using the doctrine of in articulo mortis. Which I understand to mean that a priest in extreme circumstances, may at the point of death, receive or reconcile someone into the faith.

On the night of the 2nd August 1916 he made his first confession and took his first communion. They were also his last.

It would be early on the next day, 3rd August 1916 that he is aroused. To pray, he will thank his priests, in the Gaelic “Beannacht Dé oraibh go léir. Míle buíochas as an méid a dhein sibh ar mo shon.” And he will walk between the prison warders, proudly, bravely, an Irish felon,”

Good morning Mr McGuiggan, fascinating reading. I’ve been trying to contact you, but with no success, Can you kindly get in touch with me? Thank you. Franco

Good read

Brilliant read, very informative. Go raibh math agat.